50th Anniversary, Blog

Brick Books 50th Anniversary: Brilliant and Timeless Books to Take Another Look At—Dream of No One but Myself

We’re delighted to continue our 50th anniversary series this month with D.M. Bradford’s Dream of No One but Myself. This months blog post is written by Sonnet L’Abbé.

Dream of No One but Myself

by Sonnet L’Abbé

What struck me the first time I read D.M. Bradford’s work is how powerfully their fragmented line – often refusing, it seems, to complete a full sentence – achieves an effect of contentious contact with “the big picture.” In Dream Of No One But Myself, terse, painfully observant poems about family dynamics blur into essays which disintegrate into scatterings of language, punctuated by colourful reassemblages of once cut-up photos from the author’s childhood.

Bradford’s tones manage to feel simultaneously seething and tender, as they create glimpses of themself as a bi-racial child, hypervigilant in the unreliable care of their working class parents, a “pathologically stable” white Québécoise mother and a volatile African-American father. Almost immediately, however, a footnote about how Bradford has mined their own self-harming habits and survival mechanisms to present to writing workshops suggests that the Dream we are stepping into is a document of deep ambivalence about sense-making.

Lyric poems about being the Black child of a white woman, about attempts to negotiate respect with a chronically angry but sentimental father, about processing the intergenerational trauma embodied in a vituperous, penny-pinching grandmother, and about self-presentation as a young Black man are interspersed with abstract colour visual poems, erasure poems and colour images of the “evidence” backing up the stories of a father’s coercive control and a mother’s ways of deflecting and surviving. We move between past and present, as Bradford grapples with how they navigate present-day intimacies with a girlfriend, with roommates, and with their mother now that it has been years since they have seen their father.

Dream makes many gestures of erasure and muting: longer prose passages that seem to offer frank and fulsome memories and divulgings of self-aware emotional insight appear in faded light-grey with only a few words emphatically bolded. Later in the book, another poem fashioned from bits of that prose “background text” will foreground different moments of the same passage. Other lyric passages that present at first as complete poems are later revealed to be dripfeedings of other backstories. Is this voice grasping at flashes of sense memory? Have the often-compassionate mechanisms of survival – amnesia, denial – shredded any hope for accurate recollection? Or is the author openly withholding details, exposing their own self-protection and making transparent the constructedness of poetry’s confessional modes?

There is a somewhat predictable form that many commercial prose memoirs take, in which the author’s recollected traumas figure as early obstacles to the now-thriving personal functionality that the book’s very existence “proves.” Bradford’s uneasiness with the trope of writing-as-healing, or for setting themself up as an example of having transcended an abusive upbringing, compels them to distrust existing literary forms and the expectations they enact between writer and reader. Instead, Bradford creates new forms of writing that call constant attention to their own troubling, and resist any urge to give this autobiographical exploration a smooth character arc that comes to rest in a soft place.

Bradford is breathtaking in their ability to create, like origami structures, word-built spaces in which sympathy for and validation of their child-self’s vulnerability can momentarily breathe. Then, almost as soon as they are erected, these spaces soon collapse in on themselves, under the furious weight of what cannot be restored simply by storying. A few pages later, used language is un-crumpled, and new structures and rhythms of voice breathe life, back again, into that recurring impulse that moves all writers: the impulse to connect through telling.

Get Your Copy Today – Save 25%

Order your copy of Dream of No One but Myself before October 31, 2025 and save 25% off the cover price.

Buy NowPart of the Breaking the Rules Bundle

The Brick Books Breaking the Rules Bundle includes D.M. Bradford’s Dream of No One but Myself, Andrea Actis’s Grey All Over, and Lindsay B-E’s The Cyborg Anthology. Available now at 33% off.

Buy The Breaking the Rules BundleAbout D.M. Bradford

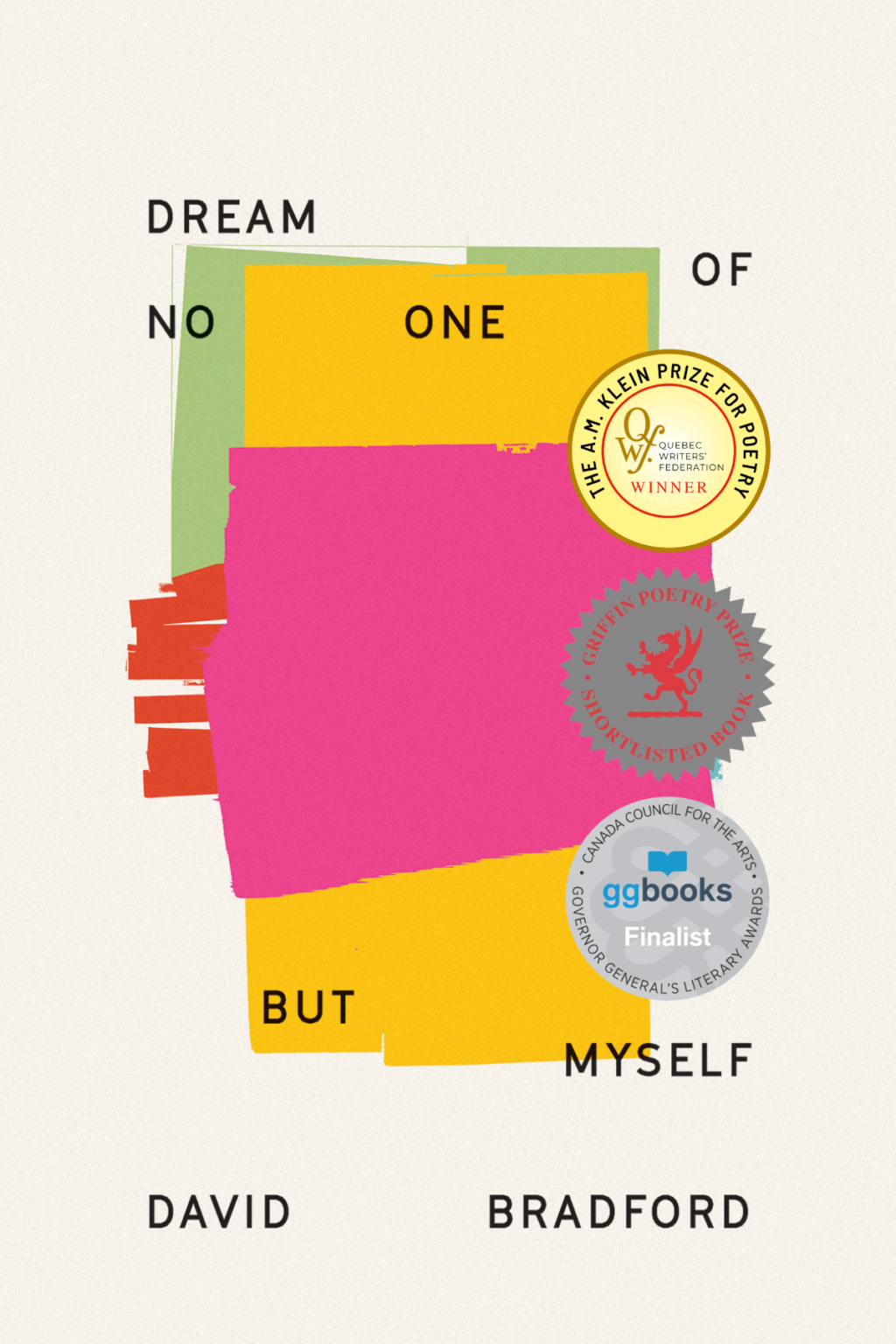

Darby Minott Bradford is a poet and translator. They are the author of the hybrid poetry collection Dream of No One but Myself (Brick Books, 2021), which won the A.M. Klein QWF Prize for Poetry, and was a finalist for, among others, the Griffin Poetry Prize and Governor General Literary Awards. Bradford’s first translation, House Within a House by Nicholas Dawson (Brick Books, 2023), received the VMI Betsy Warland Between Genres Award and John Glassco Translation Prize, and was shortlisted for the Governor General Literary Award for Translation. Their most recent book of poetry, Bottom Rail on Top, was a Raymond Souster Award finalist. Bradford lives and works in Tio’tia:ke (Montreal) on the unceded territory of the Kanien’kehá꞉ka Nation.

Nourish Your Poetic Spirit – With a Brick Books annual subscription, you receive every title we publish before they’re available anywhere else, plus exclusive subscriber perks all while supporting authors and helping to hold a place for poetry in Canada and the world.

Subscribe today.